Picturing the past, present, and future in the imaginations, dreams and journeys taken by young women in Nepal and Rwanda

Picturing the past, present, and future in the imaginations, dreams and journeys taken by young women in Nepal and Rwanda: An introduction.

Dr Marlon Moncrieffe

Theoretical Framework

The intellectual foundation that gives the theoretical framework to our study is exploring, examining, discussing and reflecting on how gender based cultural proverbs have been passed across from generation to generation in both countries, and generally in their articulating a negative portrayal of women’s representation in society at all stages of their lives (Bishwakarma, 2020; Niyonshima, 2020). For example, in examination of Rwanda, Niyonshima (2020, p.12) provides lists of proverbs where women are considered as inferior, worthless and weak people in society:

- Ntaa nkokôkazi ibîka isaâke ihâri. (A hen cannot cluck when a cock is around)

- Uruvûze umugorê ruvuga umuhoro. (A word of a woman is followed by a machete)

- Umukoôbwa w’îgicûucu yiirahiira imfîizi ya sê. (A foolish girl compares herself to her father)

- Umugorê w’înkoramwuuga, abishiima yîikoze muu nda. (A professional witch ends up in killing her own children)

- In examination of Nepal, Bishwakarma (2020) produced a survey that established a clear and substantial gap between women and humans in that society that have perpetuated the culturally accepted norm of discrimination against women. For example:

- Chhorapaye khasi, Chhoripaye farsi (A party of mutton goes on a sons’ birth, but a pumpkin on that of daughters)

- “Chhorapaye sansar ujayalo, Chhoribhaye bhanchha Ujyalo (Son brightens the entire world, while a daughter can only brighten the kitchen)

- “Swasnimanchheko buddi pachhadi hunchha” (Women are always short-sighted).

- Similarly, Jha (2008) has brought some Maithili proverbs that present women and girls/daughter negatively. For example:

- “Beta bhel loki lel, Beti bhel feki del” (Love your son, not daughter)

- “Ek beti mithai, dosar beti lai, tisar bhel tan tinu balaya” (Birth of a first daughter is good, second daughter does not bring happiness, third daughter is like poison)

- “Jehane maugi aap chhinariya, tehane lagaabaya kul bebahariya” (Innovative activities of women are always criticized)

The presentation of these proverbs from Nepal and Rwanda should not be generalised to the life experiences of all women of Nepal and Rwanda over the ages. Indeed, the resilience, self-empowerment and rise of Rwandan women to positions of power in society is documented by Hunt (2017) particularly after the genocide of 1994. Whilst for Nepal, an example of women becoming leaders in society breaking from social constraints to their gender is documented by Adhikari (2023). What this project seeks to consider and develop learning from are the more relative intergenerational experiences of women whose lives may have been framed for living according to gender discriminatory cultural proverbs. What is clear is that cultural proverbs of both societies articulate that girls/women do not matter a lot in comparison to boys/men. An internalization of this can lead to the playing out of stereotypes that can impede emancipation. Girls and Women in Nepal and Rwanda may not partake in a journey to development with those discrepancies.

Reflection and Reconceptualization

Picturing the past, present, and future in the imaginations, dreams and journeys taken by young women in Nepal and Rwanda seeks to disrupt the power of culturally embedded proverbs which perpetuate gender inequality. The purpose of our project seeks to actualise and exemplify women related to each other and of different generations. Firtsly, by their coming together and partaking in walking and bicycle journeys for finding safe spaces. In these, they can share with each other their experiences and reflections in affirming conceptualisations of their future narratives. The key objective of our project is: To support women in communicating the social challenges they have faced and their aspirations for the future.

Arts Based Methods

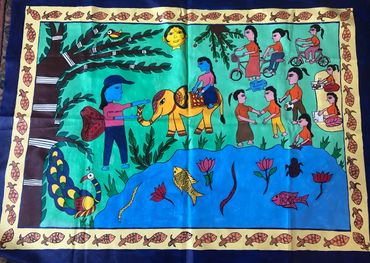

Further emancipation by the translation of the narratives given through women’s imaginations and aspirations will come through Imigongo (framed) art and photography (Rwanda) and Mithila art (Nepal).

Mithila art is a cultural form of art which depicts the ancient culture of Mithila kingdom (Central Southern region of Nepal and parts of India). This is an art form unique to women in their communication generation after generation.

There is a legend that Imigogo was invented as an interior decoration by Prince Kakira of Gisaka Kingdom in Nyarubuye in the 1800s. However, Imigogo art, is a traditionally female art form used by women in Rwanda.

References

- Adhikari, A. (2023). Substantive Representation of Women Parliamentarians and Gender Equality in Nepal. In Substantive Representation of Women in Asian Parliaments (pp. 206-225). Routledge.

- Bishwakarma, G. (2020). The Role of Nepalese Proverbs in Perpetuating Gendered Cultural Values. Advances in Applied Sociology, 10, 103-114.

- Hunt. S. (2017) Rwandan Women Rising. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Jha, K. (2008). Maithili lokokti sanchay (Maithili proverbs- a collection). Sahitya Akeademi New Delhi

- Niyonshima, P. (2020). A Sociolinguistic Study of Women Representation in Rwandan Proverbs. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 10, 24.

Young women of Rwanda and Nepal, cycling in safe spaces, discussing, and challenging gender-based discriminatory proverbs

Dr Marlon Moncrieffe

Introduction

This blog provides a brief discussion on how young women in Rwanda and Nepal have taken part in cycling journeys to safe spaces (Gayle et al. 2013) for their reflection and conversations about the impact of gender-based discriminatory proverbs on women. How could their understanding of the past informed by their interpretations of these proverbs in the present share new ways of seeing the future roles for women in communities?

The approach taken by the study to create ‘safe spaces’ for this discussion in some ways is similar to that of Harvey et al. (2020). They worked in ‘safe parks’ to ‘provide young people with a stable, safe environment’ (pg.1) supporting them to find ways to have their voice not only heard, but also listened to in a highly hierarchical society.

In Rwanda, one of the proverbs discussed by the participants was: Ntaa nkokôkazi ibîka isaâke ihâri. (A hen cannot cluck when a cock is around). This in effect meaning that a women/wife/mother for example has no voice or power in the presence of a man/husband/father.

Five questions were put to the participants to support their reflections and discussions:

- Do you recognise this proverb?

- Have you ever heard anybody say this proverb? If Yes: Who was it?

- What do you think it means?

- Do you think this proverb was true or false in the past?

- What about now and the future: How do you see the meaning of this proverb?

Some of the young women recognised how this proverb framed women as secondary to men. For example, one respondent said:

“I think the past was scary for our grandmothers as they were not allowed to express their ideas.”

There was a similar response from another young woman, who said:

“It is because in ancient time, women were not allowed to express what they think on the development of their families or other general concerns.”

However, there was a general refutation of this proverb by the young women, and sense in their belief that the past is not in the present, neither the future. For example:

“No, it is wrong, people in the past should had understood that men are equal with women.”

“For me, this proverb is discouraging as I believe girls are also capable of every job and they can do any profession.”

“This proverb should be burned because it only supports inequality which might lead to underdevelopment and depression to women and girls.”

“It is not true: as in past time, people used to underestimate women capacity but today things change, boys and girls are equal.”

In Nepal, from our cycling activities to finding safe spaces for conversation, one of the proverbs put to the young women and discussed by them was: “Beta bhel loki lel, Beti bhel feki del” (Love your son, not daughter). Many of the young women knew of this proverb. They shared how they had observed this being played out in society, and they challenged this. For example, one young woman said:

“This proverb is absolutely wrong. It is said that sons and daughters are God’s gift. But in behaviour people discriminate among son and daughter in our society. If we give continuation to these proverbs and mindset, I see our future is dark. If we change these proverbs it makes the country progress and our future bright.”

Some of the young women suggested that older generations of people were unable to challenge this proverb, but the new generation would do.

“This is wrong. But the older generation they do not know about that. This will completely vanish in future because today’s kids are so intelligent.”

“I think it (the proverb) was false. But the older generation might not understand this because they did not have any education before and no exposure. The society was like that.”

“I think it will change in future because women are doing better.”

The cycling journeys taken by these young women to these safe spaces seemed to provide a collective sense of emancipation in their bonding, in their play, in their conversations. They have provided clear voice and opinion on how culturally embedded proverbs have been able to frame women in many cases lesser than men. However, these young powerful women have given clear voice and opinion for a change of view on this representation across their families and communities.

References

Gayle, B. M, .Cortez, D., & Preiss, R. W. (2013) “Safe Spaces, Difficult Dialogues, and Critical Thinking,” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: Vol. 7: No. 2, Article 5. Available at: https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2013.070205

Harvey, L., Cooke, P., & Bishop Simeon Trust South Africa (2021) Reimagining voice for transrational peace education through participatory arts with South African youth. Journal of Peace Education, 18 (1). pp. 1-26. ISSN 1740-0201 https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2020.1819217

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.